Rules (and exceptions) of innovation

People interested in innovation—Silicon Valley founders especially, but also leaders of big businesses or researchers at business schools—are fond of reading about groups of people that invented big things. From these stories, the thinking goes, you can learn how to build a world-changing organization yourself.

Canonical stories include:

PARC: Xerox’s computing research unit that created the first personal computer, object-oriented programming, Ethernet, and the laser printer in the 1970s.

Bell Laboratories: AT&T's R&D group in the mid-20th century, particularly its basic research division, which made Nobel Prize-winning discoveries such as the transistor and information theory.

ARPA (now DARPA): an innovation program run by the Department of Defense that continues to work on military technologies, but in its 1960s heyday also created the Internet, major components of GPS, and ancestors to PARC's PC.

RAND: a government-funded think tank with leading mathematicians and social scientists that developed game theory and the foundation for ICBMs in the Cold War era.

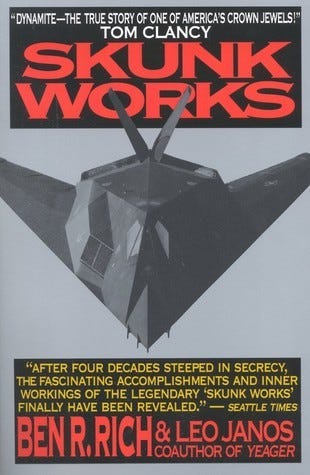

Perhaps the most popular such book is Skunk Works, about the eponymous research team inside Lockheed that created cutting-edge military aircraft, such as the U2 spy plane and the first stealth fighter. (Not coincidentally, it's also the most entertaining read of the bunch.) "Skunk Works" has become a generic descriptor for any project to focus a small team on innovation within a larger organization, although few have come close to replicating the original's success.

What I find most interesting about Skunk Works, though, is how it breaks many of the patterns from all the other stories.

The rules of innovation

Some common themes of famous research organizations include:

Stable, long-term funding. Research on the frontier of science takes a long time and requires expensive equipment, so the best organizations have ample resources and aren’t afraid of losing them tomorrow. Universities are the hallmark of this model—professors have tenure, and they're funded by predictable enrollment funds and endowments—but companies and governments can achieve something similar:

Bell Labs was funded by AT&T's monopoly profits; its mission was to find technologies that would help the parent company in 5-10 years. Thus it invested in time-intensive projects like launching the first communications satellite, which helped it transmit messages across the country more easily (until the government took control of space technologies).

DARPA is less than 1% of US defense spending, so its budget isn't under much threat. Individual projects can be defunded in theory, but according to Ben Reinhardt, about 90% last for a full 5-ish-year term; this allows program managers to form long-term relationships with leading academic or industry researchers.

No need to make profits. World-changing technologies are totally different than what came before them, so anyone working on them has a high chance of failure—and even if they succeed, it might take decades to be commercialized. If you push people to focus on the bottom line, they'll do on incremental projects that have a higher chance of succeeding quickly; that might be useful, but it's not the stuff of legends.

PARC's most famous inventions didn't benefit Xerox financially at all; its personal computer was only used for internal research (their demo inspired elements of Apple's Macintosh) and Ethernet became an open protocol. In Dealers of Lightning, Michael Hiltzer claims this reputation is oversold—PARC incubated the laser printer, which arguably paid back all of its other investments—but he doesn't deny that its leaders weren't held to any commercial pressure, allowing them to invest time and computing resources into speculative projects.

RAND set aside 1/3 of its time to work on basic research with no immediate demand; this was funded by the rest of its work (applied-research contracts with the Air Force and other government agencies).

The best talent available. Great research is naturally done by great researchers; the best organizations find them wherever they are and entice them to join by offering more money, great coworkers, or an important mission.

Per The Idea Factory, AT&T was among the first American companies to hire PhDs (previously, businesses looked for engineers who could get things done, not theorists who could find new things). And it bounced back from the Great Depression relatively quickly, enabling Bell Labs to outbid peer businesses and universities for top doctoral graduates such as William Shockley, a future Nobel Prize winner for co-inventing the semiconductor.

PARC employed basically all of the top computing researchers in the early 1970s, not only because it paid more, but also because the first hire in its computing division, Bob Taylor, already knew everybody in the field and had their respect.

RAND didn't pay crazy salaries from what I can tell, but it offered intellectual freedom and flexibility, and the mission of helping America win the Cold War attracted top talent, including more than two dozen eventual Nobelists.

Experts in lots of different disciplines. New ideas often come at the intersection of different fields, so having people with different academic backgrounds is important, as long as they bring deep expertise in their own subject.

Bell Labs employed 13,000 people at its peak, though only about 10% worked in basic research. Their backgrounds spanned subjects (chemistry, electricity, acoustics, optics, math, psychology), but there were no "departments" like in a university; Bell's campus was even designed to break down informal silos (labs were often intentionally assigned far away from someone’s office so they have to go out and see colleagues).

RAND initially focused on math but soon brought in lots of social scientists; it was structured by department, but those were blurry (according to Asterisk, an anthropologist joined the math department, and an MD joined aeronautics), and most projects involved multiple departments anyway. It grew to 200 researchers in less than two years.

A decentralized structure. A research organization can generate more ideas when individuals have the power to decide what they work on; if a boss told everyone what to do, they'd only test out the bosses' ideas (which would probably be the bosses' boss' ideas, etc).

PARC had a very flat organization—all of the several dozen computing researchers reported up to one manager—and gave everyone freedom to decide what they worked on; someone developed the first computers capable of displaying colored videos and turned it into an avant-garde collaboration with artists, even though everybody else thought he was crazy.

Unlike many government programs, DARPA lets program managers spend funding more or less however they want; each of them in turn collaborates with lots of experts in academia or business, who take on some DARPA research in addition to their other work.

Fruitful sharing of ideas. Getting challenged by peers or hearing about other ideas can inspire new directions for research.

PARC had a weekly "dealer" session where one speaker presented their work and got grilled by everybody else; Bell sponsored external lectures and education series; DARPA programs hold workshops where all the researchers get together in one place to meet each other and discuss ideas.

A different way to change the world

Skunk Works, however, breaks a lot of those rules:

Lockheed limited its investment in Skunk Works: its name comes from its original location, a makeshift office set up underneath a tent next to a smelly plastic factory, and its founder, Kelly Johnson, did it as a side project early on while fulfilling his full-time engineering duties at the parent company. So instead of doing open-ended research projects, Skunk Works had to be scrappy and fast. Its first project, a WWII jet fighter, was contracted with a timeline of six months (and was finished a month ahead of schedule); the first U-2 plane was completed in nine months.

Skunk Works spent a lot of effort managing costs—not only financially, but in wasted time. It returned $2 million to the government, 10% of its U-2 contract, for coming in under budget, and another time canceled a project when it was barely off the ground but didn't seem promising. And it used existing components and familiar suppliers whenever possible, reducing the risk that one bespoke part would delay everything. By the 1980s, Ben Rich estimates that Skunk Works alone would have been a Fortune 500-size business if it had been independent.

Johnson was a savant—he routinely estimated complex quantities outside his area of expertise almost perfectly, and he had tremendous respect from Lockheed's leadership and in the top ranks of the Air Force. But otherwise, individual talent doesn't seem to be Skunk Works' differentiator. Johnson got to pick top engineers from Lockheed, who were doubtlessly very impressive, but he didn't search far and wide for experts the way other organizations did.

And their expertise wasn’t especially broad, in part because there weren’t very many of them. The U-2 project was launched with only 25 engineers and topped out at 80 (something like 10-25% of the industry standard). This was partly due to Lockheed's desire to minimize costs, but also due to Johnson's belief that smaller teams would be less siloed and spend more time building instead of communicating.

Workers had a lot of responsibility to solve their own project, and in theory anyone could suggest big ideas, but for the most part everyone trusted Johnson to set the direction. (The best counter-example is the stealth fighter, which was suggested by a younger specialist who had come across the necessary science in an obscure paper published in the USSR; not coincidentally, that happened shortly after Johnson retired, and over his objection from the sidelines.) In fact, part of why Johnson liked working with a small team was so that it could be extremely centralized—anyone with a question or a problem could go to Johnson, and he could make the decision, eliminating all bureaucracy.

Most of their projects were highly classified, so they couldn't really engage outside experts, or even others within the company. If they needed extra help, they had to give other teams generic tasks that wouldn’t reveal what the final product might be.

How can we reconcile Skunk Works' success with the lessons above? To some extent, it shows that there are multiple ways to be innovative, which should be comforting. But there are also some ways in which Skunk Works achieved the same thing with different means:

It had freedom to choose its own direction, not because profitability didn't matter, but because Lockheed's leadership had tremendous trust in Johnson.

It avoided bureaucracy, not by having hands-off management, but by having decision-making authority centralized in one person.

It had excellent talent at least at the top, though it was recruited internally and not intentionally diverse.

It tested out ideas not by spreading them widely but by putting them into practice and iterating quickly to make them better.