Climate change is being solved

We have a ways to go, but the battles have changed

The fight against climate change has largely centered on loudly and vividly explaining how we’re all doomed if we don’t do something about it. In the past, this was appropriate: the top challenge was convincing people that climate change was a real and urgent problem, and there was in fact real doom ahead if nothing changed.

Today’s situation is different. Global warming remains a really important issue with much more progress needed, but continuing to talk about how doomed we are is fighting the last war:

Forecasting doom is no longer correct: our trajectory is bad but not apocalyptic. That's because we've made real progress against climate change already, rendering the worst outcomes very unlikely, and there's a lot of potential to make even more progress in the near future.

And forecasting doom is no longer useful. Most powerful actors already agree that climate change is important and are working toward solutions. They don't need their minds changed; they need to know the facts about what is and isn’t working, because the new battle is how to implement effective solutions. Climate change deniers have lost, and one more doom forecast won’t change their minds anyway.

My new favorite read on all of this is Not the End of the World. Hannah Ritchie, an environmental researcher at Our World in Data, writes about her own evolution from "doomer" to hopeful, which adds empathy to her analysis. She gives a data-driven assessment of the state of climate change, our current challenges, and required solutions that are sorely needed in this moment.1

The tide is turning

When climate change emerged as a major issue, things were spiraling out of control. The amount of carbon emitted into the atmosphere worldwide increased by 30% in the 2000s, driven primarily by economic growth in China and other developing countries that consumed lots of fossil fuels. In that context, it was reasonable to worry that continued global growth would inevitably cause more damage to the climate.

That runaway train has stopped: global emissions have flattened over the last five years. That's in part because rich countries have reduced emissions significantly: the US is down 20% since 2010 despite a growing population; the UK is down 40%.2 And it's in part because developing countries have slowed their growth in emissions, even though they already use much less per capita than earlier powers did at a similar stage of development.

On its own, flattening annual emissions is small potatoes: Global temperature is a function of total carbon in the atmosphere, not annual emissions, so we've merely gone from things getting more-worse every year to things getting worse at the same rate every year. In order to stop climate change, we have to get emissions down to zero (or "net zero," where we emit some carbon but offset it by removing some carbon from the atmosphere). There's still a long, long ways to go.

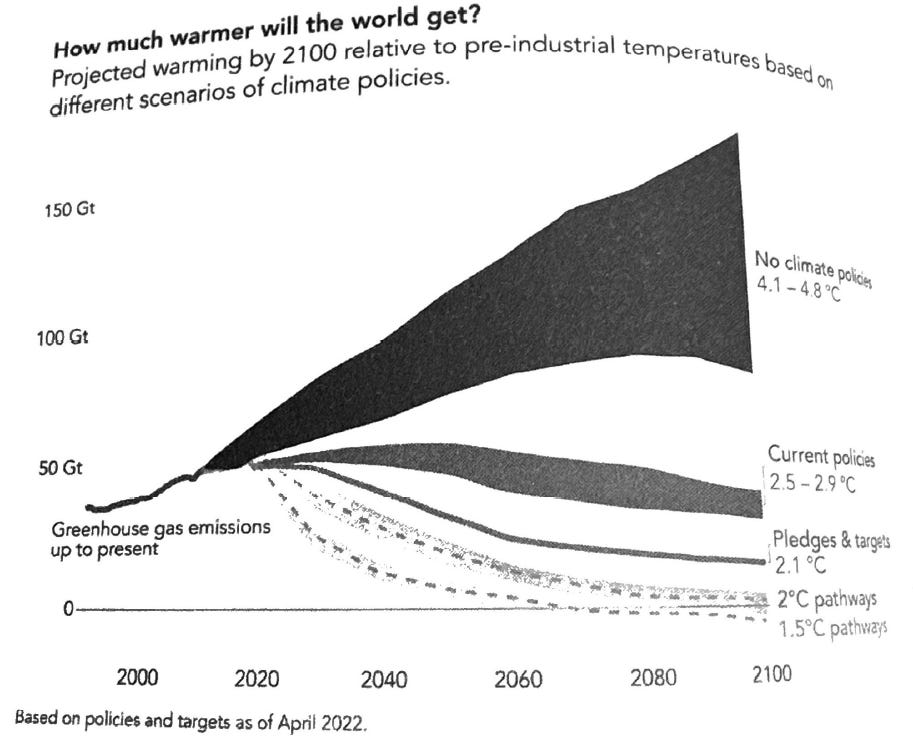

But the trajectory portends a better future. You may have seen that we're about to breach the international "1.5 degree" goal, which is true, and it's bad. But the world won't end if we pass it; things just continuously get worse as we go higher. A decade or two ago, many feared that the world would warm by six degrees or more, which would be truly disastrous: areas where billions of people live would become uninhabitable; weather patterns would become totally different; and irreversible feedback loops might take hold. Doomers still discuss those scenarios, but they’re no longer realistic: our current policies are on track for something like 2.5-3 degrees of warming; future policies that have already been pledged would get us to the low twos; and we could get below two degrees if we do even more.

What's behind this improvement? Primarily better ways of creating and using energy:

Clean energy has become much cheaper: solar costs fell by 80-90% in the 2010s, much faster than expected. Solar is now often cheaper than fossil fuels (though there are complications, which we'll get to later), prompting massive investment in new solar projects over the last three years—which should further reduce costs and emissions in the future.

Battery storage has become 50 times cheaper over the last three decades, which has made electric vehicles commercially viable. EV sales have quadrupled in the last five years, reducing the number of internal combustion vehicles (one of the top sources of emissions).

Houses, cars, and appliances have become much more energy efficient. Even with oodles of gadgets, bigger vehicles and bigger homes, the average American uses less energy today than in the 1960s.

In other words, we’re reducing emissions not just because we really want to fight climate change, but because green technologies are more effective. This means progress is happening even in places that aren’t willing to make big sacrifices in the name of environmentalism; clean energy is growing in red states like Texas and developing countries like Vietnam. And it means the world can still get richer as it gets greener—meaning more resources to invest in clean energy and to mitigate the impact of global warming that's already happened. (Contra popular belief, death rates from natural disasters have fallen by 90% in the last century; although severe weather events have become more common, we're able to prepare for and react to them much more effectively.)

The progress we've already made, and the pathway to future progress, is the biggest reason for optimism. A second, related reason is that the discourse has also gotten much better.

The battle for minds has been won

The 2021 movie Don't Look Up is about a comet that's going to destroy the world, but its creators said it's really a metaphor for climate change. It portrays businesses as greedy villains who want to minimize the problem because it threatens their interests, governments as incompetent leaders who can't admit there's a problem, and media outlets as engagement-seeking buffoons who laugh at it because it sounds crazy.

That was probably fair two decades ago, but not today. Most institutions with power not only agree that climate change is a major problem, they agree that they're responsible for doing something about it:

More than half of large businesses have pledged to eliminate or reduce emissions over some time horizon. You may think that's cheap talk done just for optics, and that's probably true in a few cases, but those are the exception: most are taking it seriously enough to base CEO pay on emissions metrics. That doesn't mean businesses are good at solving the problem yet—like any other new business challenge, this one comes without a playbook, so a lot of early initiatives are ineffective. But they're genuinely trying, and some efforts seem to be working: Walmart says it has already avoided a gigaton of emissions in its supply chain (six years ahead of schedule), while companies like Microsoft and Stripe have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on nascent carbon removal technology.

Governments around the world are also acting. The European Union passed a law mandating carbon neutrality by 2050 and to get more than halfway there by 2030. The more polarized US has done less, but not nothing: climate initiatives were a major part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including billions of dollars of incentives for clean energy and electric vehicles. China has become a leader in electric vehicle production and clean energy in large part via government incentives to shift away from coal.

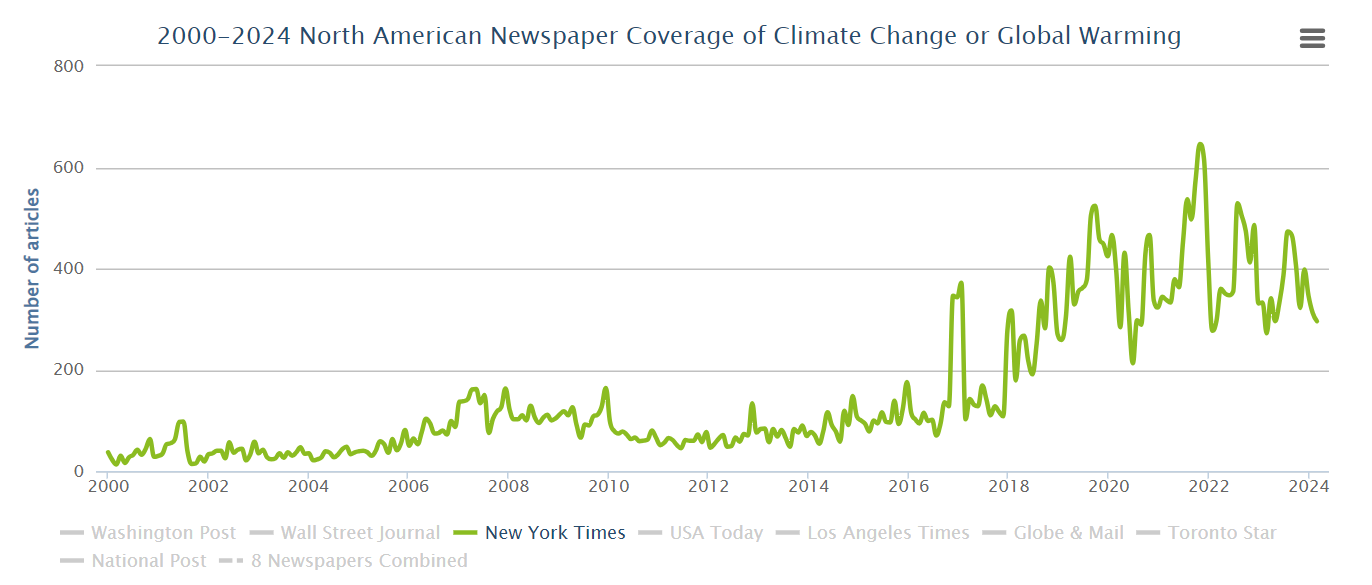

Media outlets are still engagement-seeking, but it turns out the most valuable audience is educated liberals who really care about climate change, so they cover it all the time now.

Opponents are pushing back, of course, but they don't have the power to meaningfully reverse the tide. The Trump administration withdrew from the Paris climate agreement and rolled back emissions standards, which was bad, but US emissions didn't go up during his term and kept falling afterward; a second Trump administration will do similar things, and that will also be bad, but they'll be even less effective against a stronger movement. The “anti-ESG” crusade isn't a serious force, and it's mostly aimed at social issues rather than the environment anyway; it's not going to meaningfully dent companies' commitment to fighting climate change.

(Does all this sound too good to be true—powerful interests must be disingenuous because you can’t believe they genuinely came around on the issue so quickly? Unlikely business and political leaders have helped solve important environmental issues before. When ozone layer depletion became a crisis in the 1980s, Dupont denied the scientific consensus that its chemicals caused the problem; but as it came under more pressure and had an opportunity to research alternatives, it became a major supporter of the Montreal Protocol that essentially solved the problem worldwide. And when pollution became unbearable by the 1970s, hardline Republican Richard Nixon created the EPA.)

There are still lots of climate issues with active debate on both sides—how much to prioritize different types of carbon reduction initiatives (renewables vs other energy vs carbon capture), what policies are most effective at changing behavior, how quickly we can actually transition away from oil and gas. Many of those issues are really critical for shaping our planet’s future. But almost nobody is coming at them from a perspective that climate change isn’t important, so they don’t need to be convinced of that again. Instead, disagreements come down to different analyses of how much a policy will bend the emissions curve, and different perspectives on the trade-off of bending the curve further versus other societal priorities.

Focus on details, not doom

It’s not surprising that doom messaging would outlive its usefulness. For one thing, any movement has natural inertia—most of the institutions and leaders who are most influential in the climate fight today have reached that position by changing people’s minds over the past two decades. For another, negative vibes are everywhere today.

So it’s important to have a clear perspective on the progress that’s been made and the new challenges ahead. That’s because overstating the case for doom has real downsides:

It causes unnecessary fear. According to a study of young adults across several countries, more than half say “humanity is doomed” by climate change, nearly half say it makes them hesitant to have children, and about the same share say that they think it will “threaten their family’s security” even in countries like the US and UK (not the developing, tropical countries that will be much more threatened). I don’t know how seriously to take these surveys—are people reporting true beliefs or just saying that they think climate change is bad?—but if anyone in a Western country is actually choosing not to have children because of global warming, I think that’s a shame because it’s unwarranted by the facts.3

It makes it seem like progress is impossible. Ritchie writes how she almost left environmental studies entirely because she got burned out—even after seeing so many people fighting against global warming for so long, she thought the problem was still as bad as ever. If no progress had really been made, that would be fair. But we have actually made unexpectedly great progress; we should recognize and celebrate that as a sign that our efforts are working, to encourage people to do more.

It focuses efforts on the wrong things. If you think the problem is that people don’t understand the stakes, you’ll shout at them on Twitter and think you’re doing something useful. But if the problem is actually putting solutions that work into practice, that requires a whole different form of engagement.

What are the biggest challenges in this next stage of fighting climate change? Synthesizing across Ritchie’s recommendations, I see a few important themes:

Focusing individual efforts and policies on a few big things that matter. There are lots of things that people tell you to do to help the environment, or that governments ban or incentivize in the name of fighting climate change. Ritchie says that a few of them matter much more than the rest:

Reducing gasoline use (by buying an electric car, buying a smaller car, or reducing how much you use your car entirely)

Eating less meat, especially beef and lamb

Using green energy sources

Reducing overseas flights where possible

Most other things don’t matter as much; it’s cool if you want to do them, but we shouldn’t invest much policy effort in incentivizing them:

Eliminating plastic bags, and recycling in general4

Turning off electronics, reducing appliance usage, or using energy efficient lightbulbs

Eating organic/local (this one may even be harmful on balance, because the incremental emissions of shipping food from overseas are tiny, and probably offset by the benefit of sourcing it from where it’s grown most efficiently)

Solving the challenges that can’t yet be overcome by doing more. Green energy is great, and there’s a lot more we can do with it. But wind and solar power on their own can’t solve everything yet; we’ll need to come up with new ways to use them or alternatives to doing so. The biggest examples:

Solar power produces less in the winter, and we don’t have nearly enough battery storage to smooth that out over time. This could potentially be solved by complementing it with other types of carbon-free energy (nuclear or geothermal), but political and geographic challenges are in the way.

Airplanes are too heavy to electrify, at least over long distances. Something like a solar- or hydrogen-powered plane seems possible in theory, but it hasn’t been proven.

Making concrete inherently generates a lot of carbon (separate from the energy used to make it), and right now there’s no reasonable replacement for concrete in a lot of construction. We either need some totally new material to replace it, or carbon capture technology to offset concrete emissions.

Continuing to build on the progress we’ve made. Every list of implications needs a generic, kumbaya conclusion, but it’s still true:

Now that green energy has become so cost-effective, regulatory approval has often become the gating factor for deploying it; we should put in place processes that deploy wind and solar projects with urgency.

We should keep using the tools that promoted green energy research—government subsidies, business demand, and a general vibe that it’s an important field to study—and apply them to further advances in clean energy as well as new frontiers like carbon capture.

We should continue promoting global growth and supporting low-income countries, both to adapt to the climate changes that are coming and to invest in the green technologies that we’ll need to prevent them from getting worse.

The book covers several other environmental challenges besides climate change, but the implications are similar everywhere: it's a big problem; we've already made some progress; and there's a clear path to making a lot more progress, with a few big things that really matter and a lot of smaller things that don't.

These numbers can be distorted by emissions produced in other countries that export products we consume, Ritchie says trade data studies find this would explain 10pp of the reduction at most.

This is an example of a general phenomenon: most advice is only read by the people who don’t need it. Lots of people need to be convinced that climate change is important, but the only people who will click on articles about how climate change is important are the ones who already think it’s really important, so they end up overestimating how doomed we are.

These do help fight a different environmental priority, plastic pollution in the oceans, but not nearly as much as you’d think. Recycling plastic isn’t very effective because it degrades quickly, so most plastic can only be reused once or twice, and for less valuable purposes. And in developed countries, landfills are really effective, so plastic waste almost never gets in the ocean unless you’re actually littering on the beach. (It’s a much bigger issue in developing countries that can’t afford quality landfills.)