If you browse the pop psychology shelf of your local bookstore, practically half of the books you see will have this message: The greats in any field didn't get there just by being naturally gifted, they got there by practicing a lot. Therefore, if you want to become great at what you do, you need to work hard and practice too.

And practically 49% of the books you see will support that message by citing Anders Ericsson’s research. Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise is Ericsson’s attempt to claim some space on the shelf for himself; while it engages in some of the usual speculative storytelling (it's pop psychology, after all), it adds some helpful nuance that's missing from other books.

Take the infamous “10,000 Hour Rule” that Malcolm Gladwell describes in Outliers, which draws heavily on Ericsson’s study of elite violin students. Ericsson says that Gladwell isn’t necessarily wrong about the big picture, but he’s sloppy in the details of translating his findings. (Lots of people say that about Gladwell, but as the guy who actually did the research, Ericsson gets to jump to the front of that line.) After listing some surprising-but-ultimately-trivial errors in translation,1 he gets to the fundamental flaw with the 10,000 hour rule and other retellings: in order to become an expert, you need to not only practice something for a long time, but do so with a particular type of training, which Ericsson calls deliberate practice.

Here's the catch: You can only do deliberate practice for skills with well-codified training programs, like mastering an instrument or winning at chess. For most of what we spend our lives doing, deliberate practice is literally impossible!

So why is it worth writing about? You can still apply some elements of deliberate practice to become better at learning anything. This takes a bit of creativity and a lot of work, but technology like ChatGPT shows signs of helping.

Deliberate practice improves your mental models

So what kind of practice is deliberate practice? Ericsson’s criteria:2

Specific goals ("play this sonata without any mistakes")

Immediate feedback on mistakes ("I messed up the high notes in the fourth measure, I'd better work on that section more closely")

Progressive difficulty ("once you've mastered that sonata, play this slightly harder one")

Tasks that demand full focus (not "I can play this tune in my sleep")

A coach who can guide you through a well-developed curriculum

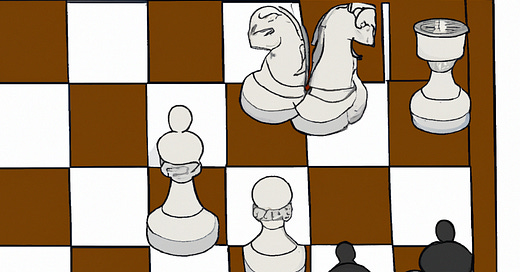

Why are these elements necessary? The key factor distinguishing experts from mortals is that they have more advanced mental models of their field. A classic example: chess grandmasters have a tremendous ability to memorize where every piece is on the board, allowing them to play out complicated scenarios in their heads and determine the best move. This isn't because they have a superhuman memory in general; it's because they’ve developed a taxonomy of common boards and key characteristics, so they can match the current situation to those and then fill in the details. We know this because, if you arrange pieces randomly on a board instead of a snapshot from an actual game, suddenly grandmasters are no better than mortals at remembering them. (According to psychology teachers, this was a surprising finding at the time, but we do the same thing every day: you'll struggle if I ask you to memorize "ajaj ilukkpx snwhzifn wiz ppqn bzodb"; but you'll easily recall the same-length sequence "your grandfather answered the door naked," because you can compress all the characters into one easy-to-remember concept.) For violinists, key mental models might include interpreting sheet music, knowing where your fingers should move to play a note, and recognizing when it’s off-key.

The tenets of deliberate practice help you build mental models. By getting immediate feedback on when you’ve failed at a goal, you know when your mental model was off-base and how to correct it. By challenging yourself and putting in effort, you can advance from simpler models to more complex ones. And by following a curriculum, you can accelerate the process by incorporating what others have learned instead of deriving everything from trial and error yourself.

Can we prove that deliberate practice is necessary? Not really. Ericsson hammers home anecdotes that show some kind of practice is necessary; stories of savants who don’t need practice are usually omitting critical details (see this very long footnote for more3). But his attempts to show the special role of deliberate practice are less convincing.

Ben Franklin was a great writer because he developed his own tedious training exercises to mimic experts’ prose and argumentation, but he sucked at chess despite playing a lot because he didn’t practice the right way? (That’s a generous interpretation of the original source Ericsson cites, which shows he did in fact challenge himself, play with focus, and study chess theory.)

A study shows that doctors don’t improve at their jobs in general once they start working full-time, but another study shows that they specifically improve at surgery, a task that requires full focus and gives immediate feedback? (Surgery would still seem to miss two of the criteria — operations don’t get harder over time, and surgeons don’t get ongoing coaching, although perhaps they should.)

The most compelling argument is: look at any field where you can objectively determine the best performers, and they’re probably using deliberate practice. Elite violinists or elite athletes all tend to take the same lessons and train in the same way; even niche areas like speedcubing have common frameworks to learn and progressively difficult exercises to master.

This is part of what causes the “10,000-hours” confusion in the first place: Ericsson’s famous violin study didn’t actually measure anything to do with how the students practiced, only how many hours they put in! He defends this by saying that all violin students were already following deliberate practice — getting one-on-one coaching from experts, doing lots of focused practice, and setting challenging goals — so the only variation is in how much deliberate practice they were doing, which is correct. (This was a program for advanced students; those of us who just practiced on autopilot and ignored our instructors had already plateaued and dropped out long before.)

What to do when deliberate practice is impossible

Whatever its other merits and flaws, Peak is a very motivating book—now I really want to go deliberate-practice my ass off and become great at something!

But ... what? I don’t have any interest in becoming a world-class violinist or chess player; the things I want to do better are a lot fuzzier, like writing or parenting or working effectively in a larger organization.

If you’re the regional branch manager at Dunder Mifflin, the criteria for deliberate practice don’t hold:

Though you get some objective feedback (weekly sales, quarterly profitability, employee morale), it’s far from immediate, and it’s often hard to connect to individual actions.

There aren’t many widely agreed best practices to learn from in management.

Good coaching is rare and somewhat out of your control. If you’re lucky, your manager will be someone who succeeded in your role before and is willing to spend time helping you learn from their experience; if you’re unlucky, your manager is a cocaine-fueled temp who leapfrogged you.

One answer is to focus on training sub-skills that do meet the criteria for deliberate practice. For example, if I want to become a better writer, I can spend time working on typing faster. That may sound trivial, but there's a good argument that typing is the most important skill for writers: the faster you can get words from your head onto the screen, the more time you have for thinking, experimenting, or finishing your work and moving on to what's next. I actually did this (more on that another time), and I think focused practice on one sub-skill can be useful at times, but there’s no way you could become a great writer just by picking off low-hanging fruit like this.

And even if you could, you start running into the issue of time. Fields like music, dance, and sports have a very strong practice culture — experts have spent an order of magnitude more time training than performing — which makes deliberate practice useful. But that’s not the case in most occupations; you have to spend the vast majority of your time actually doing your job, with a little bit of time to do focused training if you’re lucky.

For those jobs, Ericsson says, you can mix deliberate practice into your normal work. If you’re giving a presentation to your team, pick one goal that’s a bit outside your previous capabilities — say, speaking slowly and clearly enough that everyone can follow you — and rehearse your presentation with that goal in mind. Then, share that goal with your audience before your presentation, so you can get feedback immediately after the presentation on that aspect (especially from the more experienced presenters). If that goes well, pick a slightly harder goal next time, and go from there.

Though this is the point that’s most important for 90% of readers, Ericsson doesn’t elaborate it any further, burying this section in a small part of a middle chapter. Fortunately, psychologists Peter Fadde and Gary Klein have filled that gap with a great framework called deliberate performance. You do your normal work (the "performance" part), but in a way that creates as many of the characteristics of deliberate practice as possible: repetition, immediate feedback, incremental challenge, and mentorship.

They give four alliterative archetypes:

Estimation: Before starting any task, predict how long it will take (or even better, break it into sub-tasks and predict each of those). As soon as you finish the task, you’ll get objective feedback on whether your prediction was good or bad. Not only is accurately estimating timelines a very useful skill on its own, but by noticing what you do get wrong and figuring out why, you'll improve your mental model of how things work. You can get even more practice by doing this for your coworkers' projects too (although I don’t recommend mentioning this after you correctly predict they'll miss their deadline).

Experimentation: Instead of doing a recurring task the usual way, try a different approach and see what happens. Even if the experiment "fails" and the new way doesn’t work as well, you’ll understand the causes and effects better.

Extrapolation: Talk with your coworkers about their successes and failures, so you can learn from what they have learned as well. This could also include playing out counterfactual scenarios like "what would have happened if we did X instead" or "how could this have gone even worse."

Explanation: After a project succeeds or fails, try to figure out why it went the way it did. This works best with a little bit of coaching from someone more experienced: first try to come up with the reasoning yourself, and then share it with someone who has more context or has seen similar things happen more, and learn from where their explanation differs from yours.

Most of these exercises involve specific goals and feedback, helping you build more advanced mental models. They’ll naturally get more difficult as your career advances (estimating an individual task is easier than estimating a long, multi-team project). And they require your full focus—which is why they’re powerful, but also why doing them doesn’t come naturally to begin with.

ChatGPT can help

Did I add this section just so I could add “ChatGPT” into the title for clickbait? Yes. But it’s also true: large language models can help overcome the inertia that makes it hard to get off the ground with deliberate performance.

For example, you may want to experiment by doing something different in how you work for a week, but you might be running low on ideas for what you could do differently. ChatGPT can help you brainstorm, either very broadly (just based on your occupation) or more narrowly (to address a specific frustration).

And if you want to digest what you’ve learned from a project, but you don’t have access to a good coach, ChatGPT can do that too. Ethan Mollick has a prompt for using AI as a coach to reflect on an experience, instructing it to become a sounding board by asking simple questions that make you think about your experiences. (His exact prompt is aimed at students, but it’s easy to tailor to other circumstances.)

Using technology in this way is still brand-new and is itself subject to a learning curve. But over time, I expect that large language models will help humans learn faster, especially at fuzzier skills that don’t yet have a clear guidebook.

If you're into Gladwell-bashing, the surprising-but-trivial mistakes include:

10,000 hours is nowhere in the original study -- it actually found that the best students had averaged 7,400 hours of practice by age 18. Gladwell rounded that up by saying they were on pace to reach 10,000 hours by age 20, which is accurate but meaningless; at age 20 those students still wouldn’t have been "world-class" performers yet.

Even that 7,400-prorated-to-10,000 figure was an average in Ericsson’s study, not a minimum -- by definition, approximately half of top performers were below the supposed threshold!

And even if there is a minimum requirement, it isn’t the same across all fields. Ericsson describes a participant in one of his other studies who needed only 100 hours of practice to set a world record by memorizing and recalling 40 random digits spoken to him in a row, because who else would devote even that much time to something so arbitrary? (That's a rhetorical question; now that it's a thing you can compete in, of course people are doing just that, and the world record is now 456 digits.)

If you need even more new jargon, Ericsson calls bullets one through four "purposeful practice"; adding the fifth makes it "deliberate practice."

This book aims to add rigor to a topic that’s often discussed superficially, but that battle plan falls apart as soon as Ericsson meets the enemy of “innate talent.” Ericsson is so into the practice-beats-talent idea that he spends a lot of the book setting up and knocking down strawmen of naturally gifted performers. Usually these involve Mozart:

Prodigal performance at a young age is often chalked up to natural talent, such as when Mozart became a performance-caliber pianist at six years old. But he also practiced intensively from a very early age (his father apparently wrote one of the first books about teaching music to young children), and today you can find a hundred six-year-olds on YouTube who can play at a similar level after lots of practice, so it's unlikely that they all just have the elusive piano gene too.

Some experts are said to have been great from the very first try, such as Mozart writing his first symphony when he was eight, but these claims are usually overstated. Ericsson says those early symphonies weren't actually very good, and they were in the handwriting of his father (a trained musician himself), who claimed he was just "cleaning up" the younger Mozart's work, but come on.

Even seemingly "savant-like" abilities are usually developed by training rather than natural gifts. Mozart may have been the first person ever to demonstrate "perfect pitch" (it was written about as a novelty at the time, and I can't find anyone earlier cited as having it). But we now know that this skill can be trained, and that the people who have it coincidentally also have a lot of musical training and/or speak tonal languages where the pitch is critical for meaning.

If you don’t already buy into the practice-matters-more-than-talent theory, all this circumstantial evidence probably isn't going to convince you. I generally do buy into it, so whatever. But even if you’re convinced that innate talent is not sufficient to be great at something, however, you might still wonder if it's necessary. Can anyone become great in most fields with enough practice and opportunity, or are there inherent limiting constraints?

You won’t get a satisfying answer here. Ericsson mostly just looks at the IQ scores of people who are already experts in cognitive fields, such as scientific research and chess, and shows that among those experts, there's no correlation between IQ and success among that group. But that doesn’t address the point:

A small problem with this is that IQ scores are a pretty rough proxy to stand in for every source of natural talent that might be relevant here. (For example, one study finds that, while "intelligence" has a minimal correlation with chess performance, all "inherited talents" combined may explain up to nearly half.)

The bigger problem is Berkson’s Paradox: by only looking at elite performers, you may just be selecting out everyone who doesn't have enough natural talent in the first place. For example, if you only look at NBA players, there's no correlation between height and basketball performance -- but being taller massively increases your odds of getting to the NBA in the first place. So in basketball, it's clear that many (short) people have almost no chance of becoming great no matter how much they practice. How many other fields are like that in ways that are less visible? Ericsson makes a big deal out of how great scientists like Richard Fenman and William Shockley had IQs "only" in the 120s, so raw intelligence isn't that important. But if becoming a great scientist requires a 120 IQ (the top ~10% of the population), that sounds like a big deal!

Fine, Ericsson says, maybe there’s a threshold of raw talent required in some fields, but that could just be due to opportunity. Maybe IQ doesn't matter for actually doing research if you practice enough, but you need a high IQ to get a good GRE score, and you need a good GRE score to get into a Ph.D. program, and you need a Ph.D. to be a scientist.

Mostly, however, he wants to get away from that discussion as quickly as possible, because he thinks any belief in natural talent has bad effects: if you try piano once and you aren't Mozart right away, you might give up. Or perhaps more importantly, if you're a piano teacher with 20 students and 19 of them aren't Mozart right away, you might nudge them to go play Roblox instead and stop wasting your time. Maybe this is correct, and we're better off just believing that natural talent doesn't matter! But it’s disappointing that Ericsson doesn’t engage more deeply on a factual level.