Three-dimensional stories

This is one of the great archived videos on YouTube:

Kurt Vonnegut compresses stories into two dimensions—happiness = f(time)—and shows that a lot of famous plots look the same. Things start out fine, something bad happens, and it gets resolved? That’s a "man in hole" story: think The Wizard of Oz or Monsters Inc. Someone starts from the bottom, their life improves, it’s briefly threatened but then they live happily ever after? That’s a "Cinderella" story: think Babe or (at least in Vonnegut’s view) the New Testament. It's well worth the four minutes for his pacing and presentation alone.1

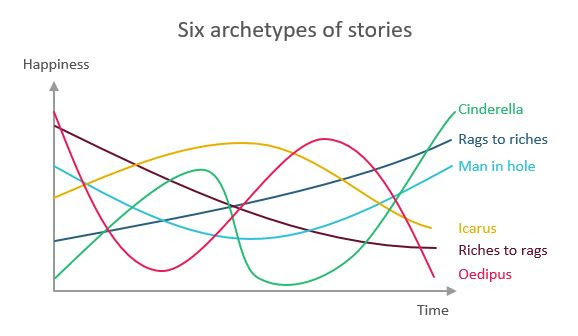

A few years ago, some researchers quantified this idea: they took a bunch of famous books, analyzed the frequency of happy or sad words throughout them, and looked at which patterns emerged.2 They found six archetypes:

Rags to riches: constantly going up

Riches to rags: constantly going down

Icarus: up then down

Man-in-hole: down then up

Cinderella: up then down then up

Oedipus: down then up then down

Not every story neatly falls into those six categories, they say, but they at least represent multiple archetypes strung together. (For example, the seventh Harry Potter book is a complex plot with many sub-stories).

Of course, we didn't need any data to know that! Those six archetypes already describe every possible combination of "up" and "down" with at most two changes in direction. If you then allow for combinations of these story types, you can describe an infinite number of ups and downs, which means you can describe any possible story. (Except for stories where nothing ever changes, but those don’t sell very well.)

And yet, the six basic plots still point at something real: there are only so many types of stories you can tell. If you rise and fall too many times, readers will start losing patience—which means that in practice, any combination of rises and falls you can think of has been done many times before.

If you want to be more original, there’s a trick: add a new dimension. You could try to use new or different emotions, but it's hard to match the emotional power of "happy or sad" to define a story. Another option is to play with the x-axis on our graphs instead—make time non-linear.

A lot of contemporary novels have multiple, intertwined timelines. A sample from my reading:

The Great Believers jumps between a group of characters in the 1980s and one of them three decades later.

Station Eleven jumps between four people’s stories at different stages of the pandemic.

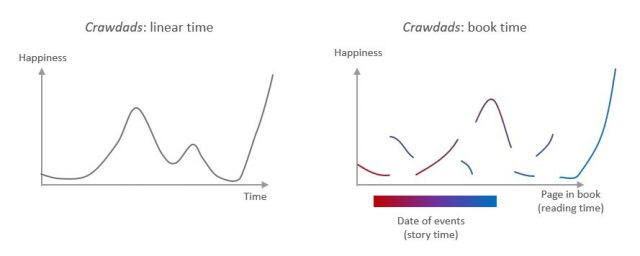

Where the Crawdads Sing jumps between the main character's backstory and a later point in time until they converge.

The Dutch House jumps between the story of the central character’s life and her future.

All the Light We Cannot See jumps between a detailed wartime scene and all the events that led up to it.

Hamnet jumps between a story of ill children and the backstory of how their family came about.

By making "reader time" different from "plot time", these novels brought in a new dimension that differentiated their plots. For example (light spoilers), Crawdads told in linear time would be a familiar Cinderella story, but in three dimensions it has a fresh and suspenseful structure:

I'm not an expert on classic literature, but I can't think of a classic novel with this structure, and a scan of Project Gutenberg's most popular books didn't seem to turn up any. I didn't find any academic studies on this question, but the few random articles and threads I found have plenty of modern examples but nothing older than Ursula Le Guin and Margaret Atwood in the late 20th century. So my hypothesis is that these non-linear novels have become popular as a way to expand the range of possible stories, because the linear ones have all been re-told so many times.3

Shapes like these don’t only apply to literature—see Sam Miller’s six shapes of baseball games.

Just analyzing whether positive or negative words were used might sound crude, but it wasn’t far from the best approach available when this paper was published in 2016. It wouldn’t be today—natural language processing has advanced tremendously, giving us e.g. the large language models that power ChatGPT and the like—but the results of the study probably wouldn’t be that different.

The Wikipedia page for nonlinear narrative lists several older works, but they don’t seem to fit the structure I’m talking about with coherent stories on multiple timelines intertwined. The examples there I’m familiar with are a) books with just a single flash-back/flash-forward, not a full second timeline; b) books with a series of single stories that don’t go in order; or c) books that are deliberately chaotic—dozens of storylines that are hard to follow—like Catch-22 or the James Joyce books. You can quibble with any of these distinctions, though.